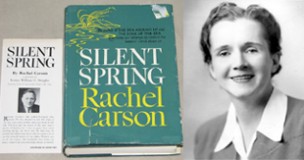

There was a time before environmentalism. In the 1950s, there was an existing view that science was the solution to everything; that humans were able to dominate the natural world. And then there was Silent Spring, a best-selling book by Rachel Carson, an aquatic biologist working for the US Fish and Wildlife Service. In Silent Spring – referring to a future with no birdsong – Carson turned her nature writing skills to warning the public about the dangers of pesticides.

Through her job she had access to many government sources who claimed their figures had been repressed or ignored by an administration too trusting of the chemical industry. Drawing on this research and that of other biologists, she drew attention to the widespread effects of pesticides like DDT – used to control mosquitoes and lice. She argued they were more properly called ‘biocides’ because they could kill or damage whole ecosystems, as well as animals other than the ‘pests’ they were designed to control.

The ecological studies she quoted indicated, for example, that increasing the use of DDT was causing bird populations to drop. Carson was also concerned about the growing resistance of many insects – including the potentially deadly malaria-carrying mosquito – to the only weapon that could control them.

Research has shown that some of the results Carson mentioned were less worrying than they seemed. But her courageous stance in presenting facts and figures in the face of government opposition and accusations of being a ‘hysterical woman’ remains inspirational. Carson’s achievements are all the more remarkable because throughout her career she had to care for her mother, two nieces and great nephew in tight financial circumstances. Her bravery and persistence – Silent Spring was released while she was undergoing radiation therapy for breast cancer – motivated much support for the environmental movement. Thanks to her insistence on measurements and impartial judgement, the environment became a political concern.