The purpose of a presentation is to communicate – nothing else. Get the basics right and your audience will engage with what you have to say.

THINK COMMUNICATION. Your objective is to communicate, rather than to impress your audience, so pitch it at a suitable level. Seeking common ground with the audience at the start of the talk will establish a good rapport; they will not mind being reminded of things they already know before going into new material. Ensure that you meet the specification. If you are asked to give a presentation on a topic in science, a talk about astrology or aromatherapy will not do!

As with written work, delimit your talk carefully and start preparation for it early so that you can improve the logic of your presentation by redrafting your first efforts, especially in the light of comments from an audience of critical friends after a practice talk. It is important to practice – certainly the real thing should not be the first time you have given the talk – but do not ‘over-practice’ since then it may sound like you have simply memorised your talk and are delivering it on auto-pilot. The templates in PowerPoint provide a good starting point for first drafts. Define all technical terms (do not assume your audience will know what emf is, or what amino acids are), but do not get bogged down in detail. Be ruthless and cut out all unnecessary material. Start with a BANG to capture your audience’s attention. Note that transitions between slides and built-up bullet points in “live” PowerPoint presentations will slow you down and should be used sparingly and only if they are needed. Do not use sound effects (accelerating car noises and the like).

Know what you are talking about! Bluffing will not work and will insult and alienate your audience. Prepare contingency plans; if it is group work, any group member should be able to give the talk, “live” presentations on PCs should have backup, talks should not entirely depend on working demos or experiments. If necessary, check your equipment in good time and take extension leads for power, internet connection etc. Have an alternative plan for when things don’t work or take longer than expected. Never download a presentation from an email address – it can take a lot of time to get logged in etc. during which your audience will have lost the will to live.

Speak loudly, clearly and not too fast. Sound interested in what you are saying (if you aren’t, why should you expect your audience to be?). Don’t sound laid back or cool. Avoid jokes unless they are really good (and suitable!). Don’t wear a coat when speaking – look at though you actually want to be there!

Be assertive! Maintain eye contact with your audience (N.B. this is impossible if you read a prepared text). Demand their attention by varying your voice to stress the main points and use your hands. Do not apologise, giggle, scratch, sniff, try to hide behind the computer etc. Stand still somewhere where all your audience can see you and the projection, for example to the side of the screen and back from the computer. Address the audience, not the computer or the screen. If you are nervous, hold a pencil – it gives you something to do with your hands and de-stresses you!

Slides

Never read your presentation from a prepared text – it is extremely boring for your audience. You need to do something extra in an aural presentation to make it worth the extra time it takes, since even slow readers can read much faster than you will be able to speak.

Use slides with a few key phrases and diagrams to provide you with visual cues on what to say next. (Additional material not on the slide can be written briefly on cue cards to remind you of the next point.) It is quite possible for your audience to read material from the slide and listen to you at the same time, so you should expand and explain your slide content rather that simply repeat it. Use colour logically to link similar ideas, logical connections or classes of items together. Avoid yellow and orange, which cannot be seen. Use a pastel background and a strong font colour. You can’t please everyone, but many dyslexic people find black on white difficult to read. Some of your audience members may be colour blind so avoid combinations like red/green, silver/blue etc. Do not put more than a few lines on each slide. NEVER use a font size of less than about 20 ppi – it cannot be read. Remember the chance of all your audience having good eyesight is slim! Here is a guide to creating effective PowerPoint presentations.

You may be surprised at how little you can say in the time allowed, so start immediately. Typically you will want two to three minutes per slide. Practice your talk (actually saying all the words) with a friend first. Try out the talk again after any substantial changes. You need to be ruthless in what you cut out, but you should put important cut material on extra slides which you can use if you have enough time, or in the question time. Equally, know which slides to leave out if you have less time than you think, but be sure to include an adequate introduction and the conclusions. Put your title, name, department and year on your first slide. For talks outside your university, you should also include your university’s name and your email address.

Structuring your talk

State the topic or problem you are going to talk about clearly. State what applications it has and why it is interesting. Give a map or plan of your talk so the audience does not get lost. Indicate your priorities. Then present the main points or results in each section. Define any technical words you use but do not go into details which are better read by the audience, such as mathematical proofs, experimental procedures etc. (unless these are what your talk is about!). If you need your audience to have the structure and details after the talk, prepare a handout.

Use diagrams and pictures as much as possible – they convey more information in a short time. People understand visual clues better than words in general … we say “Ah I see it all now!” when we understand something, and this is not a coincidence. Give your conclusions together on the same slide if possible. This will end the talk with a bang and make clear to the audience exactly what their ‘take-home’ messages should be. Keep this short or you will lose the impact. Consider adding a ‘Recommendations for further work’ slide, if only to show that you know there are other related issues, extensions or applications that could/should be covered. Presentation topics are seldom, if ever, finished completely so this reflects a mature reflective attitude (and hence get you better marks). Finish with a list of references or a bibliography, which can be displayed during the question time so that your audience can copy down details if they want them.

Give the audience the opportunity to discuss the points you have raised by asking if anyone has questions. It is usually necessary to repeat any question so that all the audience hears it clearly and so that you can confirm it – this also gives you time to think about your answer. Have a board marker handy to sketch/write your answers. If nobody has a question, you could amplify one or two of the main points in your talk or cover omitted items. You could ask the audience about things you don’t know yourself. Even if you can’t answer audience questions, it is a good sign if people have questions since they have at least been listening and were interested.

In short your talk should look something like:

- Title, your first name and SURNAME and student id number

- Plan of the talk

- Introduction – why the problem is important or interesting (including possible applications)

- CONTENT including slides on

- definitions of terms

- assumptions

- the mathematical model if appropriate – preferably done diagramatically e.g. flow chart

- main equations (two or three only for general talks – more for specialists)

- solution techniques if really necessary, but only the main ideas with few details usually

- results – use graphs and pictures in preference to numbers

- Conclusions – these need to be defensible based on what you have said and are certainly not afterthoughts!

- Recommendations for futher work

- Bibliography or references

Your lecturers will probably be able to offer advice if you ask; here’s a very useful handout about Communication Mathematics by Prof John Beasley.

About the Study Skills pages

These pages were originally created by Martin Greenhow.

Study Skills by Martin Greenhow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Study Skills – Time Management

Study Skills – Projects and Essays

Study Skills – Using Charts and Graphs

Study Skills – Postgraduate Research

Image Credits

Featured Image by Alex Litvin on Unsplash

Earth Day Presentation (CC BY 2.0) by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

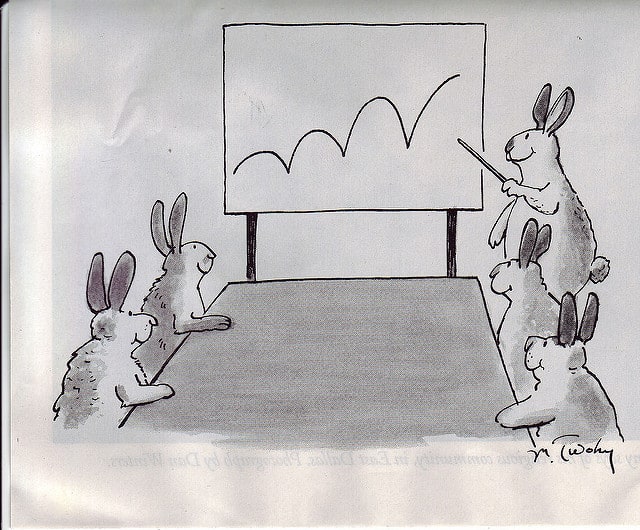

presentation (CC BY-NC 2.0) by russelldavies