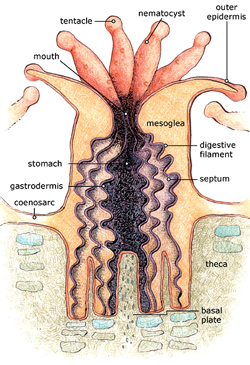

Underwater coral reefs are often mistaken for rocks or plants, but in fact they’re made up of millions of tiny animals called polyps. These creatures’ cylindrical bodies are are just a few millimetres in size, with a mouth at one end surrounded by tentacles. The polyps live in colonies, sucking calcium out of the seawater to create a skeleton around themselves, and it’s these skeletons that form the beautiful coral reefs. Only the surface of the reef is actually alive, as living polyps build their skeletons on those left behind by dead ones.

The polyps’ coral reefs are sometimes called the “cities of the sea” because they provide a habitat for thousands of other species. Although reefs cover less than one percent of the ocean floor, they support about 25 percent of all marine life. This includes microbes that share a symbiotic relationship with the coral polyps, providing them with energy through photosynthesis in exchange for a place to live. Unfortunately this wealth of biodiversity is under threat from climate change, but a mathematical model could help scientists protect it.

The polyps’ coral reefs are sometimes called the “cities of the sea” because they provide a habitat for thousands of other species. Although reefs cover less than one percent of the ocean floor, they support about 25 percent of all marine life. This includes microbes that share a symbiotic relationship with the coral polyps, providing them with energy through photosynthesis in exchange for a place to live. Unfortunately this wealth of biodiversity is under threat from climate change, but a mathematical model could help scientists protect it.

Decline in the deep

All over the world, from the Great Barrier Reef in Australia to reefs in the Caribbean Sea and Indian Ocean, coral is rapidly declining. Marine biologists think that rising sea temperatures are the cause, as both coral and the organisms it supports are very sensitive to temperature changes. If the surrounding water gets too warm the microbes inside the coral are expelled, and as these microbes provide coral with their amazing colours, this leaves it white or bleached. It can also allow hostile microbes or pathogens to take over, infecting the coral with diseases and ultimately destroying it.

To understand how these diseases take hold, biologists at Cornell University in the US created a mathematical model describing how the population of microbes changes over time. The microbes live in a sticky layer of mucus that surrounds the coral, and normally the beneficial microbes produce antibiotics that ward off any pathogens. Changes in the environment can break this mutual relationship however, leaving the coral open to infection.

Underwater models

The model consists of two differential equations that encompass all these factors:

Here b and p stand for the number of beneficial and pathogen microbes in the mucus layer, while

s = 1 – p – b

is the amount of mucus left unoccupied. The two functions fb and fp contain information about factors such as the microbes’ growth rates at different temperatures and the effectiveness of the antibiotics in combating the pathogens.

Writing these functions out explicitly is complicated, but we can easily say some general things about them. Both functions increase when s increases because microbes spread into free space within the mucus, but fp decreases when b increases because a great number of beneficial microbes means an increase in antibiotics.

It turns out that during colder months the beneficial microbes outdo the pathogens, creating a stable equilibrium where only they can survive. When the weather warms up, the pathogens can actually grow faster than the beneficials, but the effects of the antibiotics keeps them in check. It’s only when there is an unusual heatwave that the pathogens become dominant, because the beneficials stop producing antibiotics at higher temperatures. Once this happens it’s hard for the situation to go back to normal, and the pathogens continue to dominate even at lower temperatures.

It turns out that during colder months the beneficial microbes outdo the pathogens, creating a stable equilibrium where only they can survive. When the weather warms up, the pathogens can actually grow faster than the beneficials, but the effects of the antibiotics keeps them in check. It’s only when there is an unusual heatwave that the pathogens become dominant, because the beneficials stop producing antibiotics at higher temperatures. Once this happens it’s hard for the situation to go back to normal, and the pathogens continue to dominate even at lower temperatures.

Cleaning up coral

The model shows that even a gradual rise in temperature can lead to a sudden change in which microbes are dominant, allowing hostile pathogens to take over the coral and kill it. Preventing this switch is key to preserving coral reefs, but that could be a challenge in a warming world. It might be easier to improve water quality around coral reefs, making it harder for pathogens to take hold in the first place. More detailed mathematical models and future research could lead to other solutions, and help keep the crucial coral reefs alive.